Written by Eric Bronson

On Friday May 19th at Seattle City Hall, YWCA Seattle|King|Snohomish hosted its annual Stand Against Racism event, bringing together city officials, poets, activists and community members to take the pledge against racism and to hear how structural racism presents a barrier to achieving stable shelter for those experiencing homelessness.

Keynote speaker Dr. Donna Beegle, President of Communications Across Barriers, spoke about her upbringing as a migrant laborer on farms across America and the “generational poverty” that had trapped her and her family into a homeless existence. She spoke of how the people who understand her best are those who have also experienced generational poverty, because they see the pressures that prevent people from rising out of that poverty. Generational poverty though, as Donna reminded us, is not equal across race.

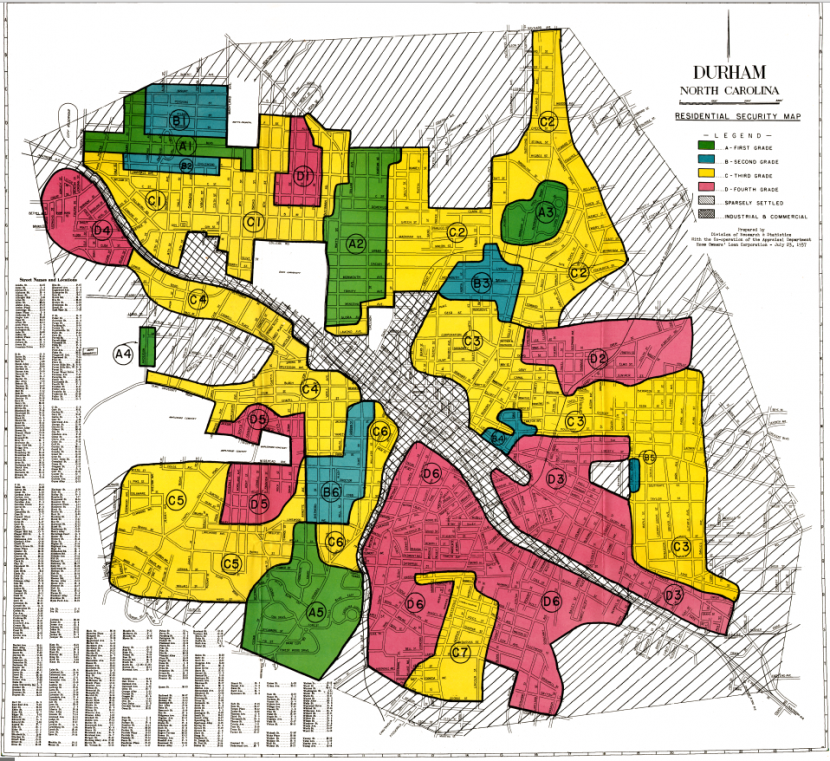

Perhaps nowhere is this distinction in poverty by race more apparent than in the historical process of “redlining.” Under the New Deal, Congress created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to provide loans for homeowners to pay their mortgages. Before the FHA provide the loans, it had to assess all of the housing parcels to evaluate their value. Each level of financial risk was associated with a color that was used on the zoning map to indicate whether or for how much a house was eligible for loans. Red was the color used for the worst of all housing stock; recommending no loans were given. As such, redlining was the process by which the FHA auditors circled every majority-Black neighborhood in America’s cities with a red pen, excluding the residents of those neighborhoods from the government loans that unlocked the incredible wealth-generating power of homeownership for white Americans. So two families living across the street from each other in poverty at the beginning of the century, one White and one Black, would have totally different experiences driven by the inequity of housing policy. This inequity has since been inherited by subsequent generations of Black Americans, as wealth is generational and the largest wealth creator for most Americans is their home.

The policy of redlining not only prevented Black Americans from achieving the same upward economic mobility as was afforded to whites, but it did so in a way that made its cause difficult to perceive. Politicians would spend the next century blaming the victims of this policy by declaring that it was a lack of work ethic or motivation that kept people of color in poverty and housing of poor quality. It is the invisibility of institutionalized racism to precisely the people who benefit from it that makes it so insidious.

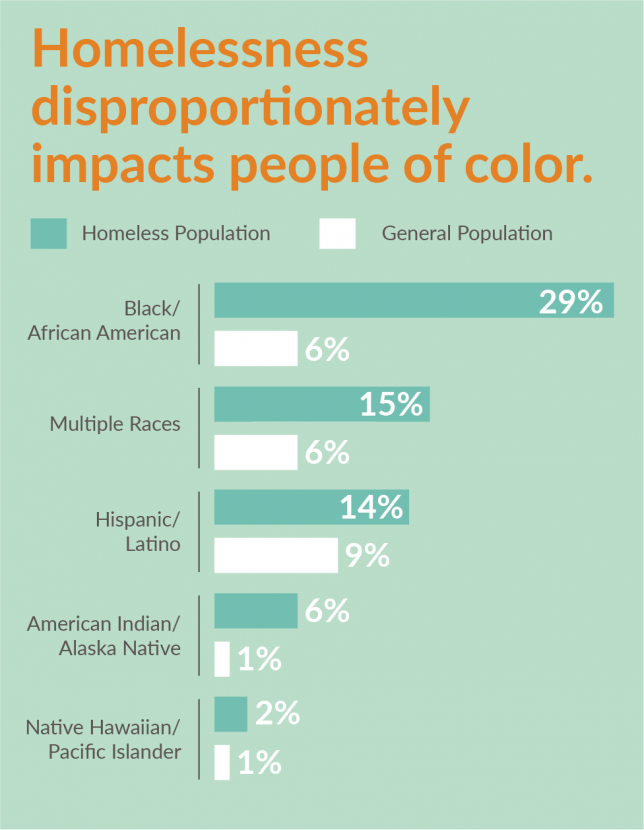

Today the effects of those discriminatory policies are still felt, in the wealth and income gaps of Americans, and in the disproportionate number of African Americans who are homeless in King County. Despite comprising only 6% of the total population, Black and African American King County residents make up 29% of those experiencing homelessness:

One of the ways in which housing policy today fuels these disparities and sets up barriers by race is through source of income discrimination (SOID). SOID is the practice by landlords to deny persons seeking to rent property who have Section 8 housing choice vouchers. Section 8 holders only have 6 months to find housing before the voucher expires, and in a housing market at tight as the one in the Puget Sound area, SOID often means that they are unable to find a landlord to accept them. This practice is currently legal state-wide in Washington, and it affects the predominately Black applicants and current residents of Section 8 housing. Toya Thomas, a mother from Renton who has a Section 8 voucher that she uses to help her pay rent while she cares for a child with mental illness, received an eviction notice from her apartment manager at Renton Woods Apartments stating that she would have to go because of her disability insurance income.

As Toya points out in her speech, seventy of the families evicted from Renton Woods wereAfrican American. Is it really so surprising that a disproportionate number of our community experiencing homelessness in King County are Black when the very program designed to keep low-income folks in housing is being intentionally subverted? Understanding how the historic racism of redlining led to inequities of wealth for Black Americans is critical to understanding how SOID discrimination today disproportionately comes to fall on Black Washingtonians.

Just as we saw with “redlining,” some are still pointing fingers at the victims. Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson said last week that “poverty is just a state of mind.” Positive thinking may be a noble ideal, but hard work and positivity could not magically undo the redlining and denial of FHA loans to black homeowners in the past, nor can it do so for those facing SOID today. Toya being denied housing because her landlord discriminated against her for having disability insurance is not a state of mind, it is a reality for millions of mostly Black Americans across the country.

What will end racially discriminatory practices like this is concerted advocacy in our state legislature to make such policies illegal. YWCA Seattle|King|Snohomish is leading the fight to ban SOID in Washington State, and we encourage you to add your voice to ours in making this change a reality. Sign our letter here to your legislators in Olympia to encourage them to pass SOID protections as a part of their final special session package.