By Perry Firth, Graduate Student, Seattle University Community Counseling, and Project Assistant, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness

Many of us intuitively understand that our childhood impacts us as adults. It is not unusual to find ourselves doing the things our parents did, for better or worse.

Over the past decade, data has emerged showing that our childhoods affect us more than previously thought. Not only do they affect our adult mental health, but they can also lay the groundwork for our long-term physical health. It’s all part of a fascinating framework called Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs. This may have staggering implications for children who experience homelessness.

Adverse Childhood Experiences: Deepening our understanding

Because I was interested in learning more about what our childhoods mean for our adult health, I attended the NW Children Fund’s event on Adverse Childhood Experiences and Building Resilience, March 6 at Seattle’s Town Hall. The event also featured speakers from Brigid Collins Family Support Center in Whatcom County; Jumping Mouse Children’s Center in Jefferson County; and Parent Trust for Washington Children, a statewide organization.

I was looking forward to gaining a better understanding of the relationship between traumatic events in childhood, and what those events mean for children as they grow into adults. Specifically, I was hoping to answer the question, What are the long-term impacts of homelessness in childhood?

This question is both a natural extension of my interest in trauma, anxiety and adolescence, and a reflection of my work with family homelessness as an assistant with the Project on Family Homelessness. I can also thank Paul Tough’s acclaimed recent book, How Children Succeed, for my interest in ACEs. Much of his reporting on the impacts of chronic stress on struggling youth drew on the idea of ACEs. (Mr. Tough will visit Seattle on April 5; more below.)

You also might have seen a recent column by Jerry Large in the Seattle Times, about how one educator is using ACEs to better handle disruptive students. People are talking a lot about ACEs right now, but where did they come from?

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) is a term that grew out of a study initially conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente’s Health Appraisal Clinic in San Diego from 1995-1997. The study was designed to get a better understanding of the relationship between stresses and trauma in childhood and what these experiences mean for adult physical and mental health outcomes. The ACE study has continued, and in many states is now in the process of gathering state-specific information, making it one of the most comprehensive studies ever conducted. In fact, new Washington state data was announced at this workshop, and I’ll discuss it below.

The 1995-1997 wave of the study enrolled more than 17,000 adults who were seeking routine healthcare through Kaiser, to answer questions about any traumatic childhood experiences. These adults answered questions about what sort of negative events they had experienced as children, and what that meant for their current mental and physical health as adults.

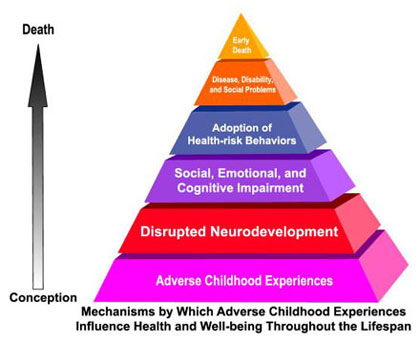

What these participants revealed has changed how researchers, doctors, and therapists thought of not only the real causes of poor adult health and health risk behaviors, but early death as well.

What the researchers realized was that many official causes of death, like cancer, smoking, AIDs, heavy drinking, or diabetes, can actually be a result of the underlying trauma many people have experienced in childhood.

This begged the revolutionary question, What is the actual cause of early death? If, for example, someone started smoking in an attempt to soothe the painful emotions felt as result of their childhood experiences, and continues to smoke to help regulate their dysregulated stress response system, is it really the smoking that killed them? Or is it their underlying trauma?

This was a completely new perspective, and many of those familiar with ACEs would argue that in fact, the on-going effects of childhood trauma are the actual cause of untimely death. This perspective also means that if you really want to eliminate many of the health risk behaviors in our society, you need to eliminate adverse childhood experiences.

The researchers found, for example, that:

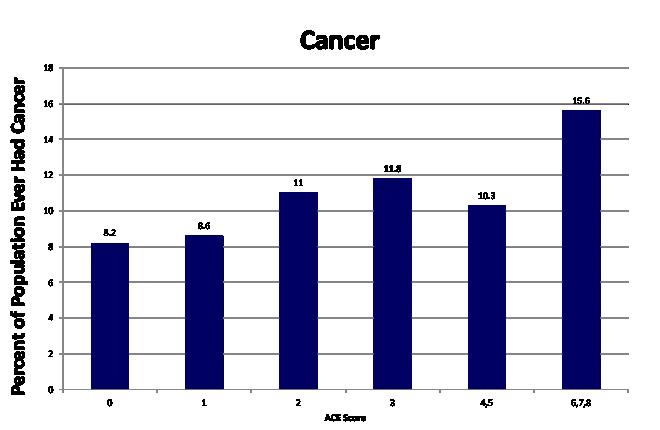

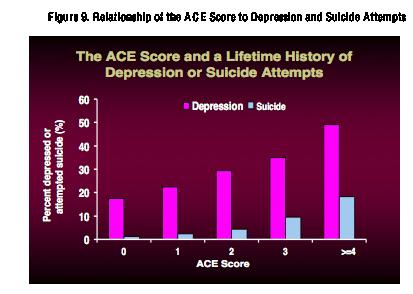

- The more traumatic events, or ACEs, an adult had experienced, the more likely they were to: smoke (and be unable to quit); use drugs; miss work; abuse alcohol; attempt suicide; develop cancer, depression, stroke, severe obesity, or diabetes; and contract a sexually transmitted disease (STD).

- People who have experienced six or more ACEs die 20 years earlier than people who have experienced zero ACEs.

The ACEs list: What would your score be?

What kind of trauma is considered an ACE? There are 10 official categories of ACEs. These categories include emotional, physical and sexual abuse; having an incarcerated relative; mother treated violently; mental illness within the family; parental divorce; substance use; and physical and emotional neglect.

For the purpose of the ACE study, each one of these events carried a score of one, allowing the researchers to add up all the traumatic events someone in their study had experienced. Each adult in their study earned a total ACE score that measured the cumulative total of the adversity they had experienced as children. A lower score meant less adversity, and a higher score meant more adversity. This ACE score provided a clear, if somewhat detached way to accurately conceptualize the amount of trauma the people in their study had gone through.

More than mental health: It’s physical

While many therapists and other people involved in the helping field have long recognized that the wounds of traumatic childhood events contribute to their clients’ ongoing mental health struggles, the ACE study added another layer to their understanding. Clearly for the first time, people realized that the social and physical health outcomes that society so desperately tries to fight and prevent – like cancer, stroke, smoking, obesity, HIV transmission, substance abuse, and poor health habits like little exercise and unhealthy eating – are for many people reactions to negative experiences in childhood, as well as reflections of an exhausted stress response system.

For many involved in this work, it felt like the missing puzzle piece had finally been found.

It was with all of this in mind that I listened to Laura Porter, the moderator of the workshop, break down ACEs, what sort of ACE scores Washington state has, and why they are important concepts for the workshop attendees to understand. Laura is the director of ACE Partnerships for the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services.

ACEs in Washington state: How do we compare?

Washington state has the honor of being among five states, along with Arizona, New Mexico, Tennessee, and Louisiana, who were the first to start looking into their residents’ experiences of childhood adversity in 2009.

Washington did this through including ACE questions on their 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a telephone survey designed to assess for health risk behaviors associated with early mortality (death).

The Washington state data that emerged from the BRFSS was, unfortunately, in line with the results from the original ACE study from the 1990s. Just as that study found that ACEs are highly interrelated in that if respondents reported one ACE, they were likely to report more, 62 percent of Washingtonians reported at least one ACE, 26 percent reported at least three, and 5 percent reported 6 or more ACEs.

Are ACEs showing up in Washington state classrooms? Sadly, yes. In the typical high school classroom in our state, 5 students have 1 ACE, 6 students have 2 ACEs, 3 students have 3 ACEs, 7 students have 4-5 ACEs, and 3 students have at least 6 ACEs. Our classrooms unfortunately reveal just how many students are carrying increasingly heavy burdens. What does this mean for their ability to just be teenagers? Or to focus in class?

At the session we also heard some breaking news about ACEs research in Washington state. Here it is: Parents who have 3 or more ACEs in their own lives are 400 times more likely to pass down 2 or more ACEs to their children. This statistic effectively highlights the inter-generational transmission of adversity and trauma.

As scary as this is, it is important to realize that adversity doesn’t have to be handed down from mother to daughter, father to son. As our society begins to grapple with the long-term consequences of ACEs, we are also beginning to look at how to both prevent them, and stop their transmission to younger generations (in fact I hope to write a follow-up blog chronicling these efforts, so stay tuned!).

Homelessness: The 11th ACE?

As I listened to Laura Porter, I couldn’t help thinking about families who are either homeless or unstably housed. I noticed that she wasn’t including family and childhood homelessness in her presentation, and homelessness had been conspicuously absent from my own research into ACEs.

This confused me. Surely the trauma of losing your home, moving from shelter to shelter or sofa to sofa, would count as an ‘adverse childhood experience.’ And as many people know who are involved in the fight to end homelessness, children in homeless families struggle in school, and are far more likely to be diagnosed with a learning or mental health disorder than a child who is stably housed.

Based on seminal research by Dr. Ellen Bassuk and others, The National Center on Family Homelessness further illuminates the potential consequences of childhood homelessness, reporting for example that children experiencing homelessness are also sick four times more frequently than a stably housed child. This statistic is a clear reflection of the stress the child is experiencing while coping with homelessness. Like the negative impact from the traumas included in the ACE study, homelessness is negatively affecting homeless children’s stress response system.

After the workshop, Ms. Porter was kind enough to address my questions about qualifying childhood homelessness as an ACE. She told me that a researcher, Dr. Chris Blodgett with Washington State University and Washington State University Area Health Education Center, uses the term adverse childhood exposure to describe the lasting impact that homelessness in childhood can have.

What Dr. Blodgett found won’t shock anyone involved with this work, or for that matter, anyone who intuitively understands the importance of stability in a child’s life. In his study of elementary children, homelessness was as equally powerful in predicting troubling mental and physical health outcomes as other traumas, such as child abuse. In this way childhood homelessness really is the 11th ACE, and worthy of as much time and resources as other childhood stresses.

Does all stress have the same impact?

A theme that I have observed in writing this piece, and that one of the workshop speakers alluded to, is that the brain doesn’t discriminate when it comes to toxic stress. That is, the brain doesn’t care what the stressful event is; it only registers the event as stressful. That is why children who are experiencing homelessness in many cases have the same chronic health outcomes as a child who has experienced abuse or neglect. If there was ever an argument for early intervention, it would be this.

All this work on ACEs and homelessness leads us here: Children and adolescents cannot suffer chronic stress indefinitely. It does change how their brain responds to both the world and their own emotions through dysregulating their stress response system. This can lead to issues with planning, problem solving, emotion regulation, memory, impulse control, and forming intimate, healthy relationships.

What do these types of issues look like in the real world? Problems learning in school, problems focusing on homework, using substances to cope with overwhelming emotions, emotional outbursts, unhealthy sexual activity and unhealthy relationships.

Extreme stress in childhood: Homelessness can be an adult outcome

Another way to look homelessness is not just to examine it from the standpoint of childhood, but to ask whether it can be an outcome of extreme stress during an adult’s youth. Questions assessing just that relationship between toxic stress in childhood and adult homelessness were added to the 2010 and 2011 BRFSS. What was revealed is that those adults who had experienced higher levels of adverse childhood experiences are also those adults more likely to experience homelessness. Adult homelessness can be the outcome of toxic stress in childhood.

This process of learning and writing about ACEs has been both exciting (I love learning about how helping professionals and community organizations continue to deepen their understanding of how best to help those in their care), and saddening. There have been moments when all of these correlations, statistics and charts feel overwhelming in their shared pronouncement: childhood trauma is bad, more is worse, and it can have lasting consequences.

But I would like to point out that every negative impact I have written about here is a preventable outcome. If we commit time and resources, there is no reason why any child or adult needs to go without shelter, mental health care, or in the case of stressed families, stabilizing parenting interventions. It all becomes a question of motivation and action. Yes, there is an uphill battle to fight. But that does not change the fact that childhood trauma is wrong, in all of its forms. So what are we going to do about it?

Where do we go from here?

What is the solution to all of these scary statistics?

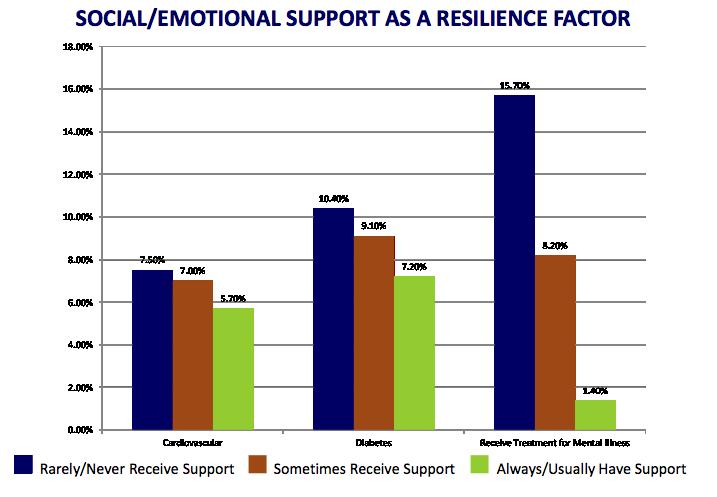

Social and emotional support are crucial in fighting the long-term impact of ACEs, as shown in the graph above, from Laura Porter’s presentation on ACEs. Notice the significant difference in cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and mental health treatment between those who never receive social/emotional support, those who sometimes receive emotional/social support, and those who always/usually receive support. In all three cases, increasing levels of social support decrease negative physical and mental health outcomes, which is why social support can be seen as a resilience factor. It buffers the impact of negative life events.

Social and emotional support are crucial in fighting the long-term impact of ACEs, as shown in the graph above, from Laura Porter’s presentation on ACEs. Notice the significant difference in cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and mental health treatment between those who never receive social/emotional support, those who sometimes receive emotional/social support, and those who always/usually receive support. In all three cases, increasing levels of social support decrease negative physical and mental health outcomes, which is why social support can be seen as a resilience factor. It buffers the impact of negative life events.

As I have said, prevention is always the best option. Let’s support legislation that provides affordable housing and rental assistance. Let’s continue to work on making access to stable housing and support services easier and less confusing. Let’s support the work of the school district homeless liaisons and the school staff who are often the first to recognize that a child is homeless. Let’s get this information out to teachers so that they have a better understanding of some the problematic behavior they can see in their classrooms. Let’s work on parenting interventions for over-taxed families that have been found to buffer the impact of stress and lead to healthier child outcomes. We can also elect politicians who care about helping families and that support funding social services.

Finally, as the graph above illustrates, consistently listening to friends and family, and showing you care, can mitigate the impact of early childhood stress. Thankfully, that is something we can all do.

We know that some formerly homeless children have become successful and healthy adults. How are they able to overcome these adverse experiences? That is something I hope to explore in another blog post. Meanwhile, if you are interested in learning more about ACEs, you can take an online course on ACEs called Reducing Childhood Experiences where you will get a more in-depth look at ACEs and resilience research.

Or you can attend a luncheon featuring Paul Tough, best-selling author of “How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of Character,” at noon Friday, April 5 at the Westin Hotel. At this event, hosted by Solid Ground, an organization working to fight poverty, Paul Tough will discuss his book, “How Children Succeed,” and touch on many of the adversities outlined in this blog.

Pingback: Storytelling, Human Connection and Advocacy: Transforming Numbers into Faces | Faith & Family Homelessness Project()